How to Support College Students Aging Out of Foster Care During COVID-19

Picture this: A second wave of coronavirus infection hits the U.S., and college leaders decide to shut down campuses. Students have two weeks or less to pack up their belongings and return home midway through the fall semester. The clock is ticking, and students from foster care backgrounds are under especially intense stress because, unlike their non-foster-care peers, they don’t have a place to call home. The absence of an immediate safety net complicates their situation, and they come to another stark realization. They are now among the more than 60% of college students who experience housing and food insecurity each year. And they are aging out of foster care. This scenario may be hypothetical, but the statistics are real.

Many colleges and universities have announced plans to reopen their campuses in the fall. But do these institutions have protective plans in place for vulnerable students in the event of another shutdown? If the recent past is any indication, many college leaders may not have adequately considered what a possible second round of closures might mean for students from foster care backgrounds. As a professor and higher education scholar, I study college pathways for young adults aging out of foster care. I have also experienced firsthand what it’s like to age out. The loss of my grandmother — who was the guardian on whom I relied for emotional and tangible support — a month before my high school graduation upended my college transition and transformed once joyous holiday breaks into times of meaninglessness and emptiness. Going home for the holidays or college breaks would never be the same for me as it was for many of my peers, who took their family privilege for granted.

That’s why I’m fighting for a higher education system that recognizes the basic unmet needs of these students and urging college leaders to develop contingency plans for this student population — particularly since the negative effects of unmet basic needs on academic achievement and persistence to degree completion is well documented. A survey of nearly 4,000 college students from 12 states found that 86% of students who experience housing and food insecurity had: missed a class (53%) or study session (54%); could not afford a textbook (55%); dropped a class (25%); or did not perform as well as they could have academically (81%).

COVID-19 impact on students in foster care

This video, released on May 1, 2020, by the National Foster Youth Institute, a nonprofit organization dedicated to improving outcomes for foster youth and their families, may give college leaders and policymakers more insight into the challenges facing these students. They already rely heavily on campus support even during times of economic prosperity. Therefore, it should not come as a surprise that many have seen their mental and physical health, employment, and safety adversely affected by the crisis and sudden closure of campuses.

Young people with a history of foster care are more likely to drop out of high school, and even those who start college are less likely to finish. This oftenoverlooked population is also less likely to have health care and more susceptible to homelessness, unemployment, criminality, and severe mental health disorders. A recent national poll of older youth suggests that COVID19 has already had a disproportionate impact on them. Over two-thirds said they had experienced financial setbacks due to the loss of employment or reduced work hours, which can negatively impact their ability to secure housing, food, and transportation. Not surprisingly, over 50% reported increased levels of depression or anxiety. Meanwhile, the possibility of another unexpected campus closure could also jeopardize students’ educational progress and attainment. Some individuals may even delay college enrollment or forgo it entirely.

Each year, 20,000 young people begin transitioning to independent adulthood, typically at or around the age of 18. However, those who are aging out of foster care are less prepared for self-sufficiency. They’re less likely to have secure support networks, stable housing and employment, medical insurance, and they’re less likely to have a safety net to fall back on during any crisis — not just a pandemic.

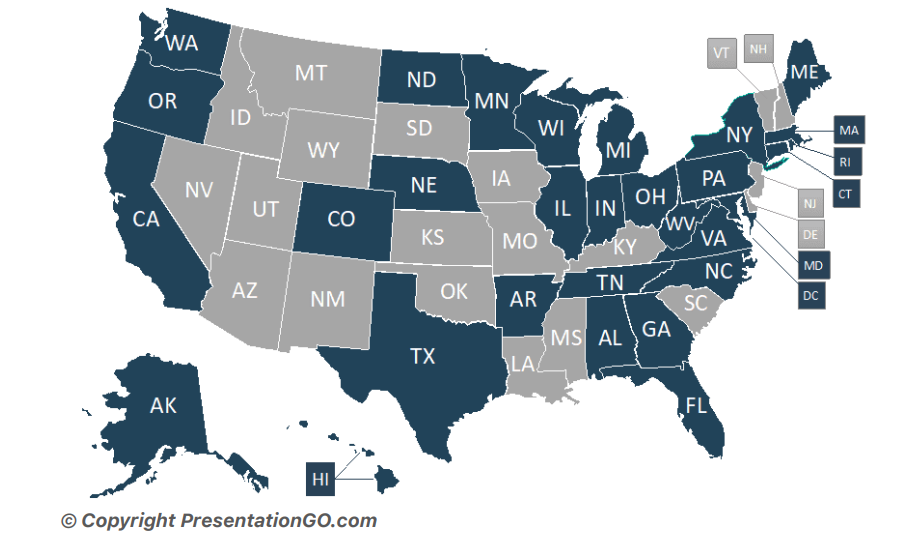

The good news is that some policymakers recognize that many 18-year-olds are not prepared for self-sufficiency, and states now have the option to provide extended foster care up to age 21. States can also provide meaningful support for older foster youth via transitional services including, but not limited to, independent-living skills training, college education, vocational training, and housing assistance through the Chafee Foster Care Independence Program. States receive federal reimbursement for services that help young people between the ages of 18-21, or up to 23 in some cases, transition to independence in states with extended foster care.

Currently, 30 states (and the District of Columbia) provide extended foster care. The bad news is that despite urgent calls for child welfare reform, 20 states have neglected to do so. As a consequence, this vulnerable population is at a severe disadvantage when it comes to transitioning to adulthood.

Many young people in foster care have high educational aspirations and expect to earn a college degree. However, the road to achieving their educational goals typically is a bumpy one. The wide disparity in college completion rates between foster youth and their non-foster-care counterparts has been well documented. In 2016, a report by the United States Government Accountability Office found that more than two-thirds of foster youth who start college do not graduate within six years.

Taking action during COVID-19

To help remove systemic barriers faced by students aging out of foster care and to promote degree completion, college administrators, state policymakers, and other concerned stakeholders should adopt a number of reforms.

- Offer students facing housing insecurity the option to remain in residence halls.

- Provide access to remote counseling services to help students coping with mental health issues.

- Establish an emergency fund to distribute forgivable cash grants to students facing basic needs insecurity or challenges in obtaining required resources for class (e.g., textbooks).

- Streamline the disbursement of emergency grants through a hasslefree application process.

- Commit to institutional evaluations using foster care status as a unique identifier.

- Enact the latest bill championed by Rep. Karen Bass (D-Cal.), which would immediately provide Medicaid to eligible foster youth until the age of 26.

- Implement extended foster care until the age of 23 in all 50 states.

- Call on Congress to increase Chafee Program funding by $500 million to help cover the total cost of attendance, including basic needs (#UpChafee).

- Waive Chafee Program restrictions that limit subsidies provided for housing.

- Make data related to these vulnerable students more transparent within federal datasets.

Since the possibility of a second wave of coronavirus hitting the U.S. in the fall is high and largely beyond our control, now is the time for policymakers and college leaders to put in place vital supports for vulnerable student populations such as former foster youth. No student should have to experience the trauma of not having food or a safe place to go when campuses suddenly close, as many students did when the pandemic first struck.

Enjoy what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive updates from Foster Youth Empowered.