It’s Time to Stop Ignoring K-12 Students in Foster Care

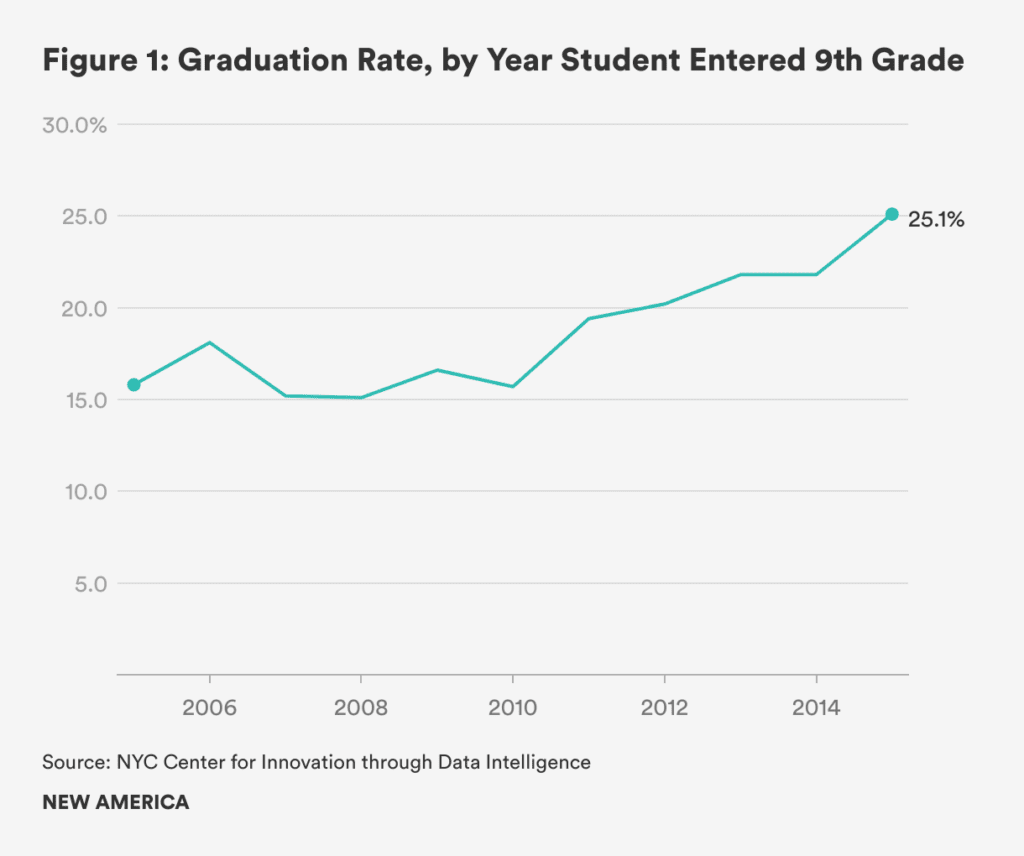

Only a quarter of New York City (NYC) youth who spent time in foster care achieved a high school diploma, according to a recent report by the NYC Center for Innovation through Data Intelligence (CIDI) (see Figure 1). By comparison, students attending NYC high schools achieved an overall completion rate of 77 percent.

Preliminary evidence from a forthcoming report from the Rhode Island (R.I.) education department found a similar pattern; that only 44 percent of students experiencing foster care graduated between 2010 and 2022.

In response to the grim statistics, R.I. state Rep. Julie Casimiro said: “These results are absolutely disgusting.â€

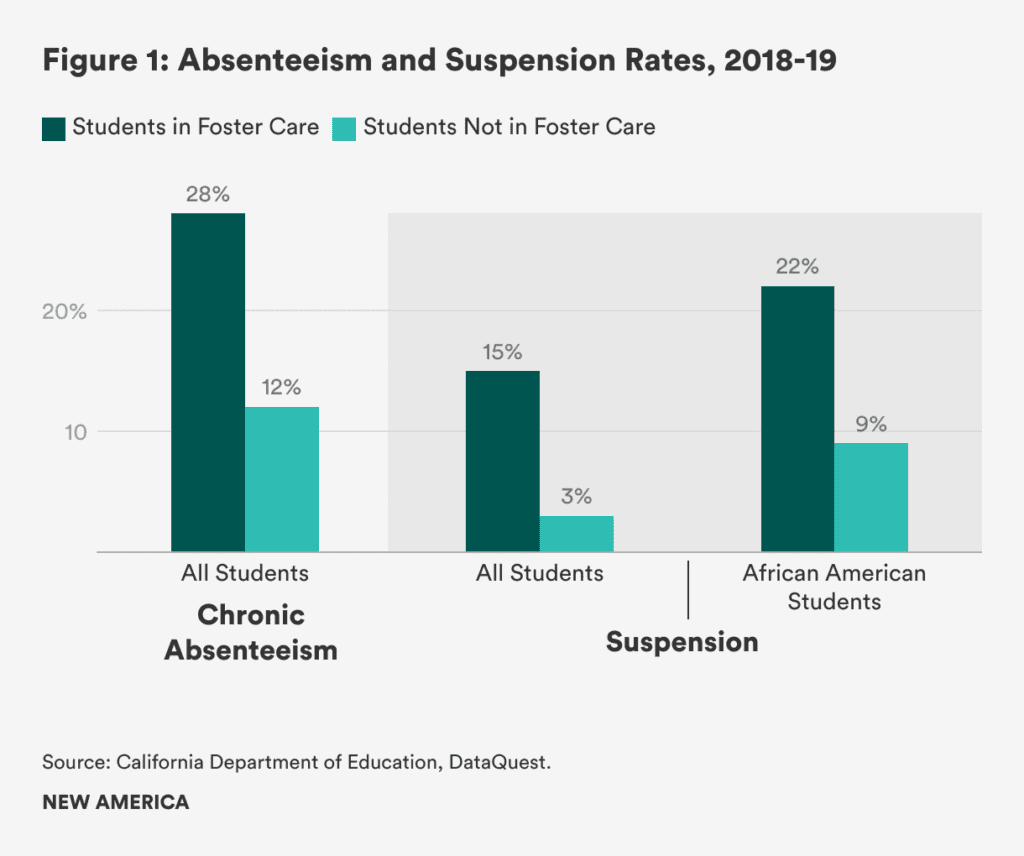

Although K-12 schools have the potential to be safe havens for students in crisis, especially young people experiencing foster care, why do foster youth continue to struggle in K-12 schools? And why have they been ignored for so long? New evidence suggests that school leaders and social services agencies must take action to promote greater parity in high school completion. Because this student population is often overlooked and underserved, state education departments must adopt greater data transparency and school accountability measures and improve coordination efforts with child welfare agencies to close long-standing inequities.

Disproportionate School Mobility

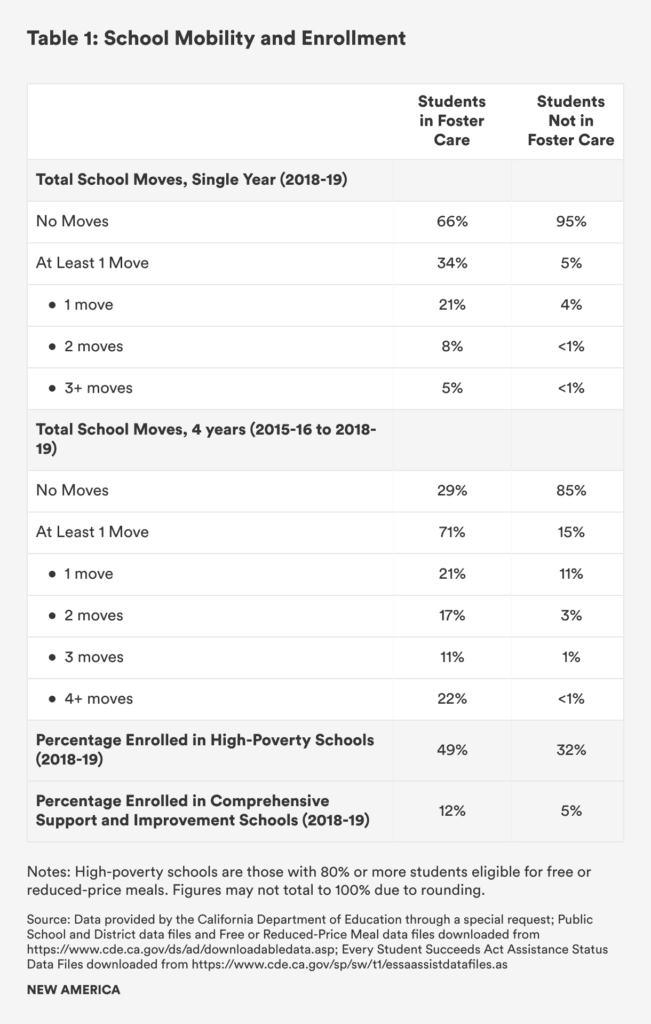

Considering how the schooling experiences for high school-aged youth in foster care may look vastly different from their peers is critical. For example, long-standing evidence suggests that young people in foster care endure severe academic setbacks due to educational instability. For instance, CIDI researchers found a correlation between high school completion and the total time spent in foster care, and the number of moves while in care. Not surprisingly, when young people spent less time in care and endured fewer school transitions–that is, less than one move every two years–the probability of high school completion increased to 33 percent. In contrast, fewer than 15 percent of youth who had two or more moves a year earned a high school diploma. A new brief from the Learning Policy Institute offers corroborating evidence on the school mobility dilemma. Analyzing school mobility among young people in care across California’s K-12 system, as illustrated in Table 1, researchers found that nearly 75 percent of these students changed schools at least once over four years; almost a quarter of them endured four or more school changes.

Enhance Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) Compliance and Oversight.

In theory, ESSA should combat the school instability issue by requiring key stakeholders to coordinate transportation for young people so they can remain at the same school they were attending prior to entering the system. Yet despite the federal law mandating that school districts provide every young person entering care with adequate transportation to their school of origin, education watchers reported that state education departments in nearly a dozen states, including New York, have struggled to enact this critical provision. To ensure ESSA compliance, the Education Department should enhance oversight by conducting audits annually and restricting Title I funding from school districts that consistently report insufficient progress in closing disproportionate school mobility rates among students in foster care.

Strengthen Education Data on K-12 Student Outcomes and Experiences.

Closing equity gaps in high school completion among foster youth requires better data collection and improved accessibility for scholars, practitioners, and policymakers. In collaboration with child welfare agencies, state education departments must revise and update current enrollment data systems to include students in foster care. While there may be valid concerns about disclosing confidential student records (i.e., Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act), California, New York, and Rhode Island have developed effective protocols for secure data sharing that meet all legal requirements and respect the confidentiality of youth and their families. State departments of education must accept responsibility for disaggregating and reporting outcomes for all historically minoritized students, including young people impacted by foster care, by replicating the same data-sharing procedures.

Despite the recent introduction of college readiness and career training programs in New York and elsewhere, it’s evident that students in foster care remain systematically barred from opening the doors of higher education even though they stand to reap the most from a college degree or credential. That said, enhancing support for K-12 students experiencing foster care can help close existing equity gaps and remove barriers to college and workforce entry.

Enjoy what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive updates from Foster Youth Empowered.